Reading Time: 11 minutes

There’s an old aphorism about being a mayor that goes, “Plowing streets isn’t a partisan issue.” In other words: Being a Republican or Democrat might signal the governing approach of a legislator or a candidate for state or federal executive office with a broad range of powers, but it doesn’t tell you much about how a mayor may manage a city. Once elected, a mayor—perhaps more than any other officeholder—is judged more on their ability to deliver results around nuts-and-bolts issues than their ability to advance an ideological agenda.

And yet so many obituaries for the late Dick Lugar note that he was a successful senator and he was a successful mayor, but fail to make the connection that he was a successful senator because he was a successful mayor. To most commentators, his eight years leading Indianapolis are merely a one-sentence biographical prelude to paragraphs about his thirty-six years of achievement in Washington.

But it wasn’t those achievements that earned Lugar the title of statesman, it was his approach to governing. And in so many of his later achievements, we see the approach of a mayor: Someone who understood that bringing people together, solving problems, and delivering results should be the goal of government, at whatever level.

In those few obituaries that do go beyond mere mention of holding the office, Lugar’s mayoral tenure is typically summarized in a single word: Unigov. But a review of the historical record shows us that his impact on the city was much more robust than government consolidation, and to focus on this issue alone doesn’t give him nearly enough credit. In studying it more closely, many readers may be surprised at what they find—but they’ll also recognize an approach to governing that is very familiar to the one Lugar adopted as a Senator when dealing with New York City’s bankruptcy, Chrysler’s loan guarantee, the Philippines, apartheid, agriculture subsidies and nuclear proliferation.

In most modern tellings of the history of Indianapolis, Lugar was the Unigov mayor, and Bill Hudnut was the mayor who redeveloped the downtown, transforming India-No-Place into India-Show-Place. This is rooted in fact: In his four terms, Hudnut expanded the Convention Center, built a football stadium and then lured in an NFL team, landed the 1987 Pan Am Games, redeveloped Union Station, rebuilt the canal, and developed the idea for Circle Centre Mall. And Unigov was Lugar’s crowning achievement, a huge accomplishment which, as Foreign Policy magazine noted last week, “made Indianapolis the nation’s 11th-largest city…and helped forestall the kind of urban decay that afflicted many cities surrounded by prosperous suburbs, such as Detroit and Baltimore.”

But to the extent that this version of history simply reduces the entirety of Lugar’s mayorship to Unigov, it’s also partially rooted in myth. Unigov was approved by the General Assembly in March of 1969, barely a year into Lugar’s first term. He didn’t exactly spend his remaining seven years in office just sitting on his hands. Instead, he developed a bold vision for the growth of Indianapolis as a world class city, starting with its downtown. The work he did laid the foundation for Hudnut to build his own well-deserved legacy.

Lugar’s first big move downtown began in secret just months after he was sworn in. He believed that a major city needed a major public university in order to build and attract an educated workforce. He was concerned that the Indianapolis extension programs of Indiana University and Purdue University were afterthoughts to Bloomington and West Lafayette, and thought Indianapolis deserved more. So in April of 1968, he met with outgoing IU President to discuss the possibility of merging the extension programs into a new university, potentially situated on the west side of downtown near IU’s medical school campus.

After Stahr retired, Lugar continued the conversation with new president Joseph Sutton and Purdue President Frederick Hovde. That December, he publicly announced he would be pursuing legislation to merge the extension operations into a new autonomous university known was the University of Indianapolis. While the legislature didn’t give him the autonomy or the name he sought, with support from IU and Purdue they did establish IUPUI as a standalone campus and appropriated funding to begin construction that same year. The first class of Indianapolis’s own public university matriculated that fall, thanks to Lugar’s role as the mastermind, the cheerleader, and the negotiator who navigated the politics of higher education to bring the two schools together.

IUPUI wasn’t the only construction project started by the Lugar administration in 1969 as the Indiana Convention Center broke ground in December. While the project was developed under Mayor John Barton (whom Lugar defeated in 1967), it would be Lugar who saw it become a reality. He also realized that without more entertainment options downtown, the city would struggle to attract national conventions to utilize the space once it opened in 1972.

Fortunately, Indianapolis already had a professional sports team, and that team was in search of a new home. The Indiana Pacers were a founding member of the nascent American Basketball Association in 1967, and were quickly proving to be a league powerhouse and a popular team in a basketball-obsessed state. The Pacers were the league runners-up in the 1968-69 season, and the 1969-70 season would see them win their first of three championships in four years. But playing their home games in the Coliseum at the State Fairgrounds, the team struggled to make money.

Lugar saw an opportunity to give the Pacers a new home in a downtown arena, which might also attract a hockey team, host concerts and other shows, and serve as overflow space for the Convention Center. All of this would help provide the much-needed entertainment options that might make the Convention Center attractive nationally. And it almost didn’t happen.

The Pacers wanted a new home as much as Lugar wanted them to have one. They didn’t want to move downtown, however, because they believed their fans predominately came from the northern suburbs. After scouting multiple locations on the city’s north side, in November of 1970 they purchased over 200 acres of land at 71st Street and I-465 in Pike Township. Having already invested in building plans, they announced construction of their new arena would begin the following April.

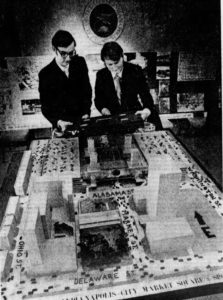

After months of city leaders publicly pleading with the Pacers to consider building downtown, the team balked at their entreaties; Lugar’s hand was forced. Just five days later, his administration made an announcement of their own: After scouting five different downtown locations, they had settled on the site next to the City Market as the perfect location for a sports arena. They, too, had building plans, which included the arena, an office building, a parking garage, and an underground plaza that could house restaurants and retailers. The price tag was $12 million, and the city was prepared to build it regardless of what the Pacers did.

As it turned out, the building plans the city unveiled at their press conference had been designed by a pair of Ball State architectural students for a school project—a clear sign that the city’s planning wasn’t as far along as the Pacers. But it was enough to bring the team to the table and convince them to delay their construction plans. After months of negotiations, a deal was reached: Market Square Arena would be built downtown, along with three private office buildings, two parks, and multiple parking garages as part of the deal. The total cost would be $32.5 million, of which the city would only be responsible for their original $12 million estimate. The rest would be financed by the Pacers and other private investors, whose property tax bills on the office buildings alone would cover the city’s $12 million bond note and interest. The cost for the Pacers to rent the arena, plus additional tax revenue that came from concessions at the arena, increased business activity in the office and commercial spaces, and increased convention activity would provide new revenue streams to address other city needs. When cost overruns threatened construction a few years later, Lugar keenly identified federal revenue-sharing funds that covered an additional $4.4 million without additional cost to Indianapolis taxpayers.

The whole ordeal was a risky gambit that looks shrewd in hindsight, especially as it resulted in a professional sports franchise locating in downtown Indianapolis. But it speaks to Lugar’s belief in the ability to solve problems by first getting all sides to sit down at the same table to talk. Further, not only would this move lay the foundation for Hudnut to later realize the potential of downtown Indianapolis, but its broad strokes would be echoed when Hudnut built a football stadium as part of a Convention Center expansion and ended up luring the Colts to come to town.

Lugar doesn’t just deserve credit for building the city up, though; he also deserves some credit for it not breaking down in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Typically, Robert Kennedy’s impassioned plea for peace during an Indianapolis campaign event with a mostly black audience is pointed to as the reason why that city didn’t see the riots that more than 100 other cities did in April 1968. Kennedy’s speech, regarded by many as one of the best political speeches in our nation’s history, clearly was instrumental in calming the city, so the acknowledgement it receives is due. However, in praising Kennedy’s remarks we have nearly forgotten the courage and leadership shown in those days by the new mayor of Indianapolis.

If it was Kennedy’s remarks that initially kept the peace, then it was largely the response of the city—working with black activists like Snooky Hendricks and Ben Bell, whom Lugar had formed a strong relationship with throughout his campaign and early into his mayorship—that maintained it. That same night, Lugar sent his staff around the city to meet with leaders of the black community, asking them to help keep things calm. The next morning, Lugar began a series of meetings of his own with black leaders, pastors, and community members. A few nights later, he gave his own extemporaneous speech on live television that lasted for a half hour. Now barely remembered, at the time the speech was praised for it’s head-on acknowledgement of racial inequality in Indianapolis. “It is not so much that we have condoned hypocrisy or cruelty or harassment, we’ve been indifferent to it,” he said. “We haven’t known about it and less have we cared. … And this is the case from which we try to unravel and extricate ourselves presently.”

Where civic leaders elsewhere were trying to downplay systemic injustice, Lugar pledged to fix it. In relaying stories he had heard from the black citizens in the preceding days that had help opened his eyes, he didn’t excuse his past ignorance but instead was willing to indict his own indifference. And he promised that the city would tackle issues like black employment, fair housing, police harassment, and desegregation of schools, to prove that in Indianapolis “human rights come first.”

Lugar’s speech (and more broadly, his approach) carried some weight in the black community in large measure because they already understood him to be a leader who listened to their concerns. That trust dated back to his time on the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners, a part of his history even less well-remembered today than his time as mayor.

When Lugar ran for the school board at the age of 32 in 1964, a group called the Citizens Committee held every seat on the board. The Citizens Committee, which took a more conservative view of education, had been criticized for not doing more to integrate Indianapolis schools. They were accused of maintaining de facto segregation, despite a state law in effect since 1949 that outlawed school segregation. Amid growing national tensions around issues of race, a more progressive group calling themselves Non-Partisans for Better Schools slated their own candidates that year, making integration their main issue.

Lugar was a slated candidate of the Citizens Committee, and quickly gained a reputation as their hardest working and most well-spoken candidate, earning himself the nickname “The Silver Tongued Orator.” On election day, the Citizens Committee would win all but one race, with State Senator John Ruckelshaus (father of the current State Senator John Ruckelshaus) the only Non-Partisan candidate to win.

With pressure mounting to address the issue of school integration, the school board sought to placate the black community by creating a new committee tasked with planning for integration. They named Lugar, the rising star of the Citizens Committee, as its chair in his first meeting on the board.

If the committee was just meant to be for show, nobody told its new chairman. Lugar began holding public meetings around the city, with a particular focus on predominately black neighborhoods. Having never been given a serious opportunity to voice their opinion with the school board before, they showed up in droves. Some meeting spaces were so full that would-be attendees had to be turned away.

When the Indiana General Assembly that met in 1965 strengthened the 1949 school desegregation law and gave schools more options for integration, questions about how Indianapolis would proceed mounted. With the help of Lugar and Ruckelshaus, Gertrude Page—the only black member of the school board—introduced and passed a resolution that required the board to publicly outline its strategies for integration. When a statement was produced by the Superintendent a few weeks later, the trio led the charge to reject it for not including a plan for integration. A much stronger statement, was adopted at the next month’s meeting.

Buoyed by this victory, Lugar continued to use the committee to push for better integration in Indianapolis schools. He succeeded in first pushing through a proposal that would allow students to attend any high school they wished as long as their was space (hoping that it would encourage black students to attend more predominately white schools), as well as a proposal that would make Shortridge High School—his alma mater that had historical been a model of integration, but recently had began to see several white families flee to the suburbs—a college preparatory school open to any student in the city who met the basic academic requirements.

For his efforts, Lugar was labeled a “liberal” by Citizens Committee supporters for “attempting to use the power of the school board” to maintain racial balance. When three members of the school board who had voted for his Shortridge plan lost reelection in 1966 because of this sort of backlash, Lugar—then serving as Vice President—lost the support he thought he had to become board president. Seemingly repudiated by his own side, a few months later he resigned in order to run for mayor. Once elected, he vowed to use his office “to prod the Indianapolis Public Schools into becoming a full partner in solving city problems.”

Ultimately, it was this fundamental notion that government has the power to solve problems that was the essence of his statesmanship and the hallmark of his leadership. This approach helped him bring together rival universities in a unique merger that created IUPUI. It brought the Pacers to the table so that Market Square Arena could be built, and Indianapolis could become a top site for national conventions. And it helped Indianapolis avoid the violence seen in so many other cities in April 1968.

Applying that same approach as a U.S. Senator made Dick Lugar one of the most consequential people in the world in the last half century. He was a U.S. Senator for thirty six years, but he was a mayor first, and always.

Selected Bibliography

- “Lugar pledges to prove ‘human rights comes first'”, published in the Indianapolis News on April 10, 1968 (page 8) [Note: Contains abridged text of Lugar’s speech in response to King assassination]

- “Lugar jabs at city’s conscience,” by Fremont Power, published in the Indianapolis News on April 11, 1968 (page 1)

- “Let I.U., Purdue in city form university,” published in the Indianapolis Star on December 15, 1968 (page 1)

- “College efforts pushed despite merger plan,” by Robert P. Mooney, published in the Indianapolis Star on January 29, 1969 (page 11)

- “Major IU-PUI on the way,” by Fremont Power, published in the Indianapolis News on October 6, 1969 (page 31)

- “Pacers unfold arena plans,” by Dave Overpeck, published in the Indianapolis Star on November 17, 1970 (page 25)

- “City agency urges arena near market,” published in the Indianapolis News on November 21, 1970 (page 2)

- “Model of downtown arena unveiled,” by Dennis Hoffman, published in the Indianapolis Star on November 22, 1970 (page 1)

- “Sports arena-office complex to be built near market,” by Robert N. Bell, Jr., published in the Indianapolis Star on April 13, 1971 (page 1)

- “Dip into revenue sharing for arena before council,” by Hugh Rutledge, published in the Indianapolis News on March 31, 1973 (page 1)

- Program from the dedication of Market Square Arena from 1974, viewed online at https://indianaalbum.pastperfectonline.com/photo/6232AF72-6B25-494F-8055-394894976808

- Thornburg, Emma Lou. The Indianapolis Story: School segregation and desegregation in a northern city. Published by the Indiana Historical Society in 1993.

- Indiana’s Visionary Statesman: The Richard G. Lugar Senatorial Papers, a digital exhibit by Indiana University Libraries at https://collections.libraries.indiana.edu/lugar/

- “Bipartisan foreign policy died this weekend,” by Geoffrey Kabaservice, published in Foreign Policy on April 30, 2019