Reading Time: 12 minutes

At the conclusion of the Civil War, Congressman Daniel W. Voorhees gave a speech in which he declared that the most important question of the day was, “Shall the white man maintain his supremacy?” Voorhees hoped the answer would be in the affirmative, but these were not the words of a bitter Confederate, or secret Klansman, or fringe lunatic; they were the words of a mainstream Hoosier politician, who in the course of his career would serve three years as the U.S. District Attorney for Indiana, nine year as a member of the U.S. House from Indiana, and nearly twenty years as Indiana’s U.S. Senator.

The words themselves are striking, primarily because the concept of white supremacy is appealed to so unambiguously. Upon hearing that phrase, modern audiences likely imagine skin-headed Neo-Nazis, or a mass of white-hoods marching under the cover of night with only their torches to illuminate the darkness. For many, it likely invokes the notion of vitriolic hatred that manifests itself in both verbal and physical violence.

But to Indiana audiences in 1865, such rhetoric wasn’t just tolerated, it actually represented widely held beliefs at the time. While it’s true that Indiana was admitted to the Union as a free state, was largely opposed to slavery, and was overwhelmingly supportive of the Union in the Civil War, this is a rather simplistic narrative of 19th century race relations in Indiana. Such an narrative ignores the thread of white supremacy that is imbued throughout our state’s history before, during, and after the Civil War. More importantly, it misses the fact that this bigotry has tended to manifest itself not through strident rhetoric and violence, but through relatively subtle words and actions—and often under the guise of routine public policy and discourse.

This can be illustrated with brief stories from three distinct eras of our state’s political history: Our founding era, when the partisan battle lines in our first popular elections were drawn around the issue of slavery; the decade before the Civil War, when Indiana rewrote its Constitution and included provisions explicitly pertaining to blacks; and the 1920’s, when the second wave of the Ku Klux Klan infamously amassed enough political power to control much of state government.

The Founding Era

Under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 slavery was prohibited within the Northwest Territory. Many of the earliest settlers into the territory came from Virginia (especially the part of Virginia that became Kentucky), and they brought their legally-owned slaves with them; those who were here before the Ordinance were grandfathered in and allowed to keep their slaves.

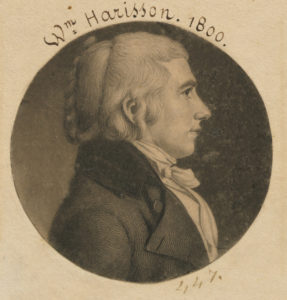

These same prohibitions were extended to the Indiana Territory when it was carved out of the Northwest Territory in 1800. This was problematic for the Territory’s new governor, William Henry Harrison, who was a slave-owning Virginian that couldn’t be grandfathered in upon his arrival to Vincennes. One of Harrison’s first acts as governor, then, was to petition Congress to suspend the slaveholding prohibition for 10 years; Congress refused, but Harrison was determined to keep his slaves. Because the Northwest Ordinance didn’t allow citizens of the Indiana Territory to elect the members of the Territorial Legislature until the adult male population reached 5,000, Harrison had the power to appoint (and thus control) its members. He stacked it with pro-slavery allies who passed the so-called “indenture law” which allowed for indentured servitude within the Territory. Then Harrison and others simply established contracts with their slaves that bound them far beyond their life expectancy, thereby evading the federal slaveholding prohibition. These contracts could be bought and sold from others, meaning slaves were freely sold here, as well.

It would be nearly a decade before Hoosiers had a chance to elect their leadership, being granted the franchise by Congress in 1809. In the meantime, slavery nearly doubled here: Census data show the number of slaves in Indiana growing from 135 in 1800 to 237 in 1810; but as many indentured black weren’t technically considered slaves, it’s likely that the number of “free” blacks enumerated in the census, which grew from 163 to 393, disguised just how many slaves there actually were. That growth would help fuel the organization of anti-slavery and anti-Harrison candidates for the first popular elections held in Indiana. The “antis” were led by Dennis Pennington, who would be elected to the legislature and chosen as the Territory’s first (and, ultimately, only) Speaker of the House; and Jonathan Jennings, who was elected to Congress that year and every year until statehood, when he was elected the state’s first Governor.

The first partisan lines in Indiana were thus drawn around the slavery issue, with Pennington and Jennings dealing a serious blow to Harrison at the ballot box. The newly elected Territorial Legislature was overwhelmingly behind Pennington, and they quickly repealed the indenture law. Harrison continuing to recruit pro-slavery candidates to oppose the anti-slavery candidates of Pennington and Jennings, and in this era before organized political parties these factions represented the broad alternatives presented to voters.

By the time the first Indiana State Constitution was drafted, the antis clearly had the upper hand: Jennings served as the State Constitutional Convention president, and Pennington was one of the chief authors of Indiana’s founding document, ensuring stronger anti-slavery language than was in the Northwest Ordinance. But being anti-slavery didn’t mean the state was racially tolerant: Only white men were given the right to vote; early state leaders quickly adopted and enforced fugitive slave laws that made it a crime to assist blacks who were still legally considered property; it was illegal for blacks to testify in court; it was illegal for whites to marry blacks; and those Hoosiers who owned slaves prior to statehood were able to continue owning them into into the 1830’s.

The 1850’s and the Run-Up to the Civil War

Over the ensuing decades, state politics began to focus elsewhere, primarily on internal improvements and other measures necessary to support a nascent state. But as mid-century national expansion drove slavery to become the most pressing federal policy discussion, Hoosiers were once again firmly in the anti-slavery camp—but they were no closer to serving as a paragon of racial tolerance.

As the national issue was peaking in 1851—just after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and just a few years prior to the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854—delegates met in Indianapolis to draft a new state constitution. Many of the delegates were concerned about the national slavery question, but they arrived at the Constitutional Convention more concerned about the number of free blacks moving into the state. As one delegate summed up the concerns, “We know that when we are overrun with them—as we most assuredly will be unless we adopt some stringent measures to prevent it—there will be commenced a war which will end only in extermination of one race or the other.”

Ultimately, the delegates opted for the stringent measures to prevent it. In addition to a nearly unanimous vote against giving black males the right to vote (only one delegate voted in support), they voted by a more than 2:1 margin in favor of what would become Article 13. That article’s first section simply read, “No negro or mulatto shall come into or settle in the State, after the adoption of this Constitution.” In addition to explicitly prohibiting blacks from settling anywhere in Indiana, Article 13 also prohibited whites from entering into contracts with blacks, and established fines for helping or encouraging blacks to move into, or stay in, the state.

Had the story ended here, it would be a deeply embarrassing episode in which perhaps only the politicians could be scapegoated. But in an unusual move, the constitution’s authors actually sent two referenda to the voters: One to ratify Article 13 on its own, and one to ratify the rest of the constitution. The vote tally exposes just how widespread racial fears were among an otherwise anti-slavery citizenry: Article 13 had more support (84%) than the rest of the constitution (80%), and in only four counties did the opposition to Article 13 outweigh the support. This article would stand until the Indiana Supreme Court struck it down after the end of the Civil War.

It wasn’t just keeping blacks out of the state that was on the mind of public policymakers at the time; they also wanted those already here to leave. The first Indiana General Assembly to meet under the new constitution directed that the fines collected under Article 13 were to be sent to a colonization fund meant to defray the cost of sending resident blacks to the relatively new colony of Libera, in Africa. To underscore how strongly they felt about this, legislators also made a direct appropriation from the state to help kick start the fund.

The notion of colonization was spearheaded by the American Colonization Society, which had founded Liberia and helped it gain independence in 1847. The Society had chapters across the country, including many county-level chapters in Indiana. They believed that blacks would be better off in Africa than in the United States, where they could establish their own society apart from whites. Among Hoosier supporters, it wasn’t uncommon to hear the corollary idea that it would also make whites better off as well. One staunch proponent of colonization was Joseph A. Wright, who served as Governor from 1849-1857. In 1862 as one of Indiana’s U.S. Senators, Wright declared the goal for Indiana through colonization was to ensure, “as far as possible, a white population.”

This is not to say these views were universal in Indiana. The large Quaker presence in the state (particularly around Wayne County) meant there were several pockets of ardent abolitionists. Like Pennington and Jennings before them, their beliefs about the evils of slavery led them into political involvement. This involvement was likely at a higher rate than other denominations, because despite making up only about 1% of the state population Quakers made up over 3% of the legislature throughout the 19th century, with roughly 150 serving as legislators in this timeframe.. But their beliefs also led them to go beyond simply opposing slavery, and they worked to display true tolerance and inclusivity towards blacks. As a result, black settlements tended to pop up near Quaker settlements, and the Quakers may be more responsible than anyone for Indiana becoming such an important route on the Underground Railroad. Levi Coffin, among its most famous participants and a Quaker, earned the nickname “President of the Underground Railroad” and helped over 3,000 blacks find freedom. But while intolerant views expressed politically in this era may not have been universal, they were the prevailing views; the Quakers were more exception than rule.

The 1920’s and the Second Wave of the Klan

These views didn’t recede in the postwar period, either. While the slavery issue was settled and blacks were granted the same rights as whites under federal law, many towns in Indiana adopted sundown laws that prohibited blacks from being out in public after sundown, or even from lodging overnight in private quarters. Many towns also established separate facilities for blacks and whites, resembling many parts of the South. But one aspect of the Reconstruction South did not come to Indiana at that time: the first wave of the Ku Klux Klan, which was almost entirely limited to the South. That would change with the resurgence of the Klan in 1920’s, however.

The story of the Klan’s influence at the Indiana State House in this decade is a well-worn one. Many are familiar with the story of D.C. Stephenson, the Evansville-based Grand Dragon who kidnapped, raped, and murdered a state employee named Madge Oberholtzer. Once convicted of these crimes, Stephenson tried to get Governor Edward Jackson to grant him a pardon. After Jackson refused, Stephenson exposed him and dozens of other state officials and legislators as Klan members, detailing to state newspapers the corruption and bribes they had been involved with. It ended many political careers, but also helped abruptly end the second wave of the Klan when tens of thousands of members fled the organization for fear of association. The Klan would later see a smaller third wave rise in the 1960s in response to the Civil Rights movement, but it was not as prevalent in Indiana as it was in the South.

The Stephenson story, replete with drama and political intrigue, masks some important points. First and foremost is that while all three waves of the Klan were ostensibly the same organization and all were based on the core belief of the supremacy of the white race, they were highly distinct in some important ways. The first Klan was made up of former Confederate soldiers who were opposing Reconstruction, broadly, and giving any rights to blacks, specifically. In this way, the third wave that fought the Civil Rights movement was its direct successor. The rhetoric of these waves was centered around the language of white supremacy and black inferiority, their tactics were based on intimidation and threats (often carried out) of violence, and their iconography focused on the Confederate flag.

The second wave, by contrast, was less overt in its use of racially charged rhetoric, its tactics more resembled a social club focused on community service than a militaristic hate group, and—very importantly—its iconography focused on the American, not the Confederate, flag. Stephenson became one of the most important figures nationally because he essentially helped rebrand the Klan to make it relevant to the era. That rebranding worked better in Indiana than just about anywhere: Indiana had perhaps the largest Klan membership in the country, with most estimates placing about 25% of non-immigrant white Hoosier males—nearly 300,000—on the Klan membership rolls, to say nothing of the thousands of white females who participated in auxiliary activities. Stephenson’s marketing efforts worked not just here, but all across the Midwest, where he was quickly placed in charge of recruiting for seven states that saw results mirroring those in Indiana.

As American society was rapidly changing—urbanization was accelerating and electricity, automobiles, and movies were relatively new innovations being quickly adopted—and Stephenson tapped into the growing angst that American society was also rapidly crumbling as it moved away from the Protestant Christian values it was founded on. This was supposedly evidenced by the bootleggers and speakeasies that flouted Prohibition, by the racy dancing that took place in jazz clubs, and the impure movies being churned out by a burgeoning Hollywood. If idle hands are the devil’s workshop, then these were the vices that made Americans idle.

The Klan was attractive to many because it appealed in patriotic terms to Protestants who thought the world was going to hell in a handbasket. They were merely helping restore America exceptionalism by participating in raids that shut down the speakeasies and the jazz clubs; by getting local cinemas to ban certain movies; by organizing politically to enact stricter prohibition laws or to fund monuments to American military strength such as the World War Memorial in Indianapolis; and by generally making America more Christian. In short, Stephenson helped wage the first modern culture war, and so persuasive was this message that many ministers extolled the Klan’s virtues from the pulpit.

Given this backdrop, it’s not hard to imagine how this second Klan wave was able to link back to the group’s core ideas. As preeminent Indiana historian James Madison notes, “The rallying cry for many patriots was 100 percent Americanism. White, Protestant Americans were true Americans standing against a dangerous surge of racial and ethnic pluralism.” Catholics, with their deference to the Pope in Rome—an undemocratic and almost monarchical figure from another country—were among the most suspect. This was especially true because Catholics tended to be immigrants who didn’t share the Puritanical aversion to alcohol that Americans did, and thus were perhaps the most responsible for moral decay. The patriotic bent also helped cast suspicions on the large number of newly arriving immigrants from Eastern Europe where the Bolsheviks were taking over: The Klan was steadfast in its fight against the specter of socialism before it could ruin American capitalism.

Though not as disdained as Catholics and immigrants, blacks were also an obvious target of this iteration of the Klan, as were Jews and other religious minorities. Blacks were considered to threaten the purity of American culture, morals, and even genetics (a growing scientific area of study) in many ways, be it through stereotypical laziness or their unique forms of entertainment, such as jazz. But as many blacks returned from fighting in World War I, they also expected to be treated as heroes on par with the white troops they had fought beside. This extended to finding employment, and many whites were anxious that returning black soldiers would displace them from their jobs. Indeed, Stephenson had served in the Army during World War I, and he found many sympathetic recruits among fellow white soldiers who struggled to find their own employment upon returning home.

Ultimately, the downfall of Stephenson caused the Klan to collapse not because members were suddenly embarrassed to be associated with these beliefs, but because they were embarrassed to be associated with the man who wasn’t the true peaceful defender of American Christian virtues he claimed he was. This is largely misunderstood today, but it helps emphasize that this form of white supremacy, like the forms that came before it in Indiana, found widespread adoption precisely because it was subtle and relatively nonviolent. And like the others, it came packaged as a seemingly reasonable extension of politic virtue and civic engagement.

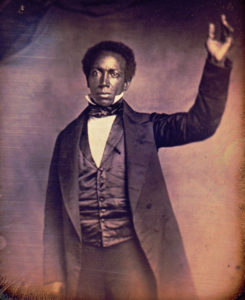

This is by no means a complete history of race relations in Indiana. It focuses only on a single thread that runs through the narrow stream of our political history, and there are other worthwhile threads and broader topics to follow. Some may show Indiana in a better light, particularly those in which blacks are the main characters of the story. Others may show just the opposite by highlighting that things haven’t always been nonviolent, such as the beating of Frederick Douglass by a white mob after he gave a speech in Pendleton in 1843, or the relative handful of racially-motivated lynchings that took place here (there are seven documented lynching events in Indiana, with 15 victims in total).

If we are to properly understand the complicated history of racial politics in Indiana, all these threads are important to follow. But the thread followed here is perhaps the best representation of the broad arc of our politics on matters of race, because it shows that the idea of white supremacy in Indiana has often manifested itself not as the violent mobs typically associated with the term, but as the mainstream politics of the masses.

Selected Bibliography

- Madison, James H. “Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana.” Indiana University Press, 2014.

- Walsh, Jusin E. “The Centennial History of the Indiana General Assembly, 1816-1978.” Select Committee on the Centennial History of the Indiana General Assembly, 1987.

- Indiana Historical Bureau. “Slavery in the Indiana Territory.”

- Brosher, Barbara. “Inquire Indiana: What’s The History Of Racism In Indiana?” Indiana Public Media, 2019.

- Fischer, Jordan. “The History of Hate in Indiana: How the Ku Klux Klan took over Indiana’s halls of power.” WRTV, 2017.